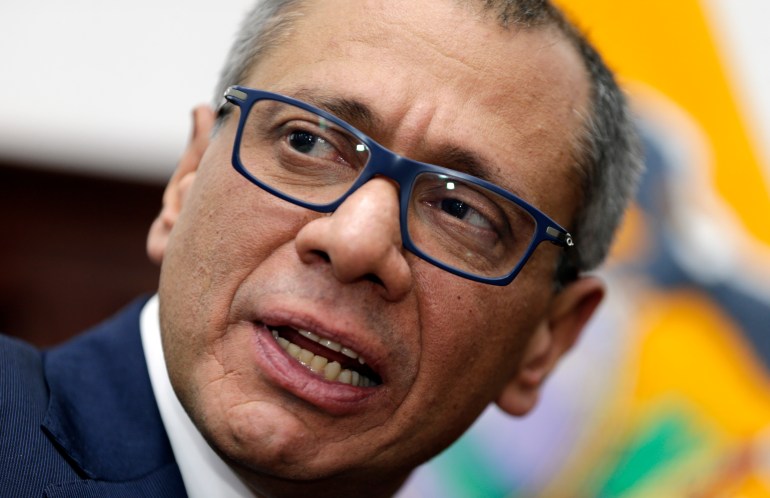

With rifles, riot shields and helmets, the Ecuadorian police scaled the white concrete gate, burst through the embassy doors and arrested Jorge Glas, a former vice president accused of corruption.

The April 5 raid on Mexico’s embassy in Quito sparked a diplomatic firestorm. Experts warned the police raid was a clear violation of international laws protecting embassies.

But in the lead-up to the raid, Mexico tried to invoke another safeguard enshrined in international law: the right to asylum.

Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, known by the initials AMLO, had announced on the same day that Glas would be granted political asylum in his country after more than three months of sheltering in its embassy.

But Glas was hardly the first politician Lopez Obrador had offered asylum to. In fact, experts say Mexico has a long and cherished history of granting asylum to figures fleeing persecution – from communist leaders to embattled presidents.

Table of Contents

Why did Lopez Obrador offer Glas asylum?

Throughout his tenure as Mexico’s president, Lopez Obrador has championed that tradition, offering asylum to fellow left-leaning politicians who face prosecution or turmoil at home.

In most cases, he portrays them as victims of political persecution and Mexico as a safe haven.

Experts and historians say Lopez Obrador uses asylum as a tool to express affinity for politicians who share a similar worldview – and to bolster his credentials as a standard-bearer for Latin America’s political left.

“Lopez Obrador has a very simple framework for understanding the political divide in Latin America with conservatives on one side and then those who are closer to what he sees as the historical mission of his government on the other,” Pablo Piccato, a professor of Mexican history at Columbia University in New York, tells Al Jazeera.

“He sees things in this way with the conservative forces of reaction against the progressive forces of the people.”

What is political asylum anyway?

Political asylum, however, is a very specific legal category. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted in 1948, lays out a right “to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution”.

Political views are one of only a handful of protected categories under international asylum law alongside race, religion, nationality and membership in a specific social group.

Applicants for asylum must make the case that their involvement in one of those categories has put them at risk of persecution or some other human rights violation – and that there is no protection to be had in their home country.

Who else has Lopez Obrador offered asylum to?

Glas is only the latest high-profile asylum case that Lopez Obrador has waded into.

For instance, in 2019, Lopez Obrador extended asylum to former Bolivian President Evo Morales after he was removed from office by right-wing forces.

Many characterised Morales’s exit from office as a coup, and Morales himself said his life was at risk.

The Mexican leader also rallied behind former Peruvian President Pedro Castillo after he was impeached and arrested in December 2022.

In the face of a third impeachment attempt against his presidency, Castillo appeared on TV and announced he would dissolve Congress. The move was widely denounced as illegal, and as Castillo tried to flee, he was detained on charges of rebellion.

Lopez Obrador, however, repeatedly tried to offer the jailed Castillo and his family political asylum, spurring tensions with Peru’s current government.

How have other leaders reacted?

The Mexican president’s use of asylum as a political tool has irked conservative leaders across Latin America, including his Ecuadorian counterpart, Daniel Noboa.

In Glas’s case, tensions between Ecuador and Mexico had been simmering for months. Glas had been holed up in the Mexican embassy since December after receiving two lengthy prison sentences for his participation in a bribery scandal.

Noboa, a right-leaning politician, had embraced a law and order image amid an increase in violent crime at home. He insisted that he would not permit “any criminal to stay free” – not even Glas.

As Mexico announced political asylum for Glas, police started to surround the embassy. Noboa has since insisted that his government did nothing wrong and he was simply exercising Ecuador’s sovereignty.

He has also disputed whether Glas was eligible for political asylum under international law.

What is Mexico’s history with asylum?

Mexico’s reputation as a place of refuge for those fleeing political persecution stretches back decades, well beyond the current spat with Ecuador.

It has even become a point of pride in the history of the country’s foreign policy:

- Those seeking shelter in Mexico have often come out of the Western Hemisphere’s revolutionary or leftist traditions. Jose Marti, the foremost figure in Cuba’s struggle for independence, spent several years in Mexico in the 1870s after being expelled from Cuba, then under Spanish rule.

- The exiled Indian revolutionary Manabendra Nath Roy fled to Mexico to evade authorities in the United States after being arrested for his anti-colonial activities in India, where he helped found the Communist Party. He would go on to play a role in the founding of Mexico’s own Communist Party in 1917.

- During the 1930s, leftist President Lazaro Cardenas offered asylum to Leon Trotsky, a central figure in the Russian Revolution who later fled threats under the government of Joseph Stalin. He was eventually assassinated in Mexico City in 1940.

- Cardenas also opened Mexico’s doors to people fleeing the Spanish Civil War. Mexico was one of the only countries at the time to send assistance to Spain’s democratically elected and left-leaning Republican government, which was locked in battle against the forces of the far-right General Francisco Franco. That put Mexico at odds with fascist leaders like Benito Mussolini in Italy and Adolf Hitler in Germany, who propped up Franco’s campaign. Mexico had undergone its own bloody internal struggle during the Mexican Revolution just over a decade earlier. Experts say its assistance for Spain signalled the country’s solidarity with the forces of antifascism abroad as it pursued a vision of economic democracy at home.

- During the Cold War, Mexico also became a refuge for those fleeing US-backed dictatorships in South America, including in Uruguay, Argentina and Chile. In their home countries, student groups, labour organisers and those deemed leftist or subversive were subjected to surveillance, torture and death. But Mexico offered a refuge.

- Not all leaders who have fled to Mexico come from leftist or anti-imperialist traditions, however. In 1979, deposed Iranian Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi spent a period in exile in the city of Cuernavaca after being overthrown by a revolution led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Mexican authorities, however, said they would not renew the shah’s six-month visa.

Have there been instances of asylum seekers being denied?

Piccato notes, however, that Mexico’s history with asylum is not without its low points.

Mexico, like much of the world, extended asylum to relatively few of the thousands of Jewish refugees fleeing genocide during World War II although Mexican officials did help some leave Europe. Only about 1,850 Jewish refugees were accepted into Mexico from 1933 to 1945.

Still, Piccato explains that it has been “a matter of pride for the country to not only give asylum but to integrate people who go on to become important figures in Mexican life”.

“It is a badge of honour,” he says.

Claudia Sheinbaum, the frontrunner in Mexico’s June 2 presidential election, is herself the granddaughter of Jewish refugees from Bulgaria who fled Europe in the 1940s during the Holocaust.

What are the political benefits of offering asylum?

Asylum can also pay political dividends for the governments who offer it.

For example, Carlos Bravo Regidor, a writer and political analyst based in Mexico City, tells Al Jazeera that Lopez Obrador has used his confrontations with right-wing governments to counteract criticism at home.

Some of the policies he has pursued sit uneasily with his image as a leftist leader. He has, for instance, dramatically expanded the power of the military and helped to crack down on immigration at the behest of the US government.

But the controversy over Glas’s arrest after Mexico had offered him asylum provided Lopez Obrador with an issue to galvanise public opinion.

“There’s a consensus in Mexico and much of Latin America that this raid really crossed a line,” Bravo Regidor says.

He adds that Noboa, meanwhile, has faced a backlash across the region. But Noboa has been seeking to boost his standing at home by cracking down on crime – and might benefit domestically.

Mexico has appealed to the International Court of Justice to expel Ecuador from the United Nations until it apologises.

How has asylum in Mexico changed?

Bravo Regidor sees the way Lopez Obrador employs asylum as distinct from the ways it was used in past conflicts.

He points out that the dissidents fleeing Franco’s Spain or dictatorships during the Cold War often faced imminent danger or death if they did not leave.

“These are people who were, without dispute, really running for their lives,” Bravo Regidor says.

But he sees a distinction between such cases and contemporary ones like that of Castillo, who was arrested on his way to the Mexican embassy to seek asylum.

In cases like the former Peruvian president’s, Bravo Regidor sees asylum as a perk for political allies trying to escape accountability.

“I think Lopez Obrador is invoking the tradition to use it as a way to help his ideological or political friends in Latin America, but he’s really devaluing that tradition in terms of the profile of the people he’s granting asylum to,” he says.

Reference :

Reference link

+ There are no comments

Add yours